By Dr. Elizabeth Ann Saunders

The work of African American educators is historically and culturally significant. African American educators helped to build and operate public and private schools, secured funding and other needed resources, worked with the African American community, and served dual but complementary roles as educators and activists for the education of African American children.

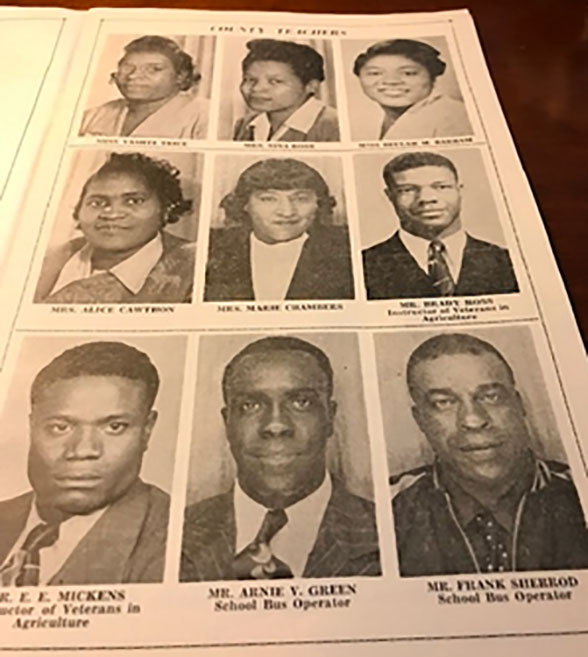

The African American teachers of Chester County Training/Vincent High School and of the various schools in the county brought benefits to the classroom beyond content knowledge and pedagogy. As role models, parental figures, and advocates, they built relationships to help students feel connected to their school. They held high expectations for the students and used connections with students and parents to establish structural classroom discipline.

We know that it’s important to not only have windows but mirrors in our schools. Students saw reflections of themselves in the classrooms. African American male teachers forged relationships with African American boys in a way others could not, and they worked together to make school work for them both.

The connection between racial justice and educational justice is permeated through effective teaching. And particularly African American teachers who have always shown up to ensure that their students were highly literate, were successful, had a positive racial identity and a sense of worth. The teachers were more than teachers. They treated their students like part of their family. They helped students stay on the straight and narrow and got many through school.

The teachers elevated their students’ confidence, taught them discipline, and created high expectations for them. The teachers were patient and nurturing and made students feel safe. The students saw role models of what was possible. Seeing the teachers in the classroom really shaped the students experiences because they gave them hope.

African American teachers made sure students saw themselves in the curriculum. No matter the subject matter, the teachers always managed to sneak in a little Black history that helped students develop a historical perspective and sense of self-worth. Students were told the stories of African American achievers such as Missourian George Washington Carver, who invented, among other things, crop rotation; Charles Drew, whose pioneering research on preservation of blood plasma saved thousands of lives in World War II; and Langston Hughes, who steeped his poetry in the rich folklore of African American life.

There was an upside to growing up in a segregated African American neighborhood: It ensured that African American teachers lived in the same communities as their students. And neighborhoods where African American teachers, janitors and domestic workers all lived together contributed to an awareness of the value of mixed-income communities long before urban planners discovered the concept.

They provided the kind of relationships, classroom environments, and expectations for students of color that helped them shine. The teachers developed an initial trust and rapport with students that help build relationships that promote learning.

As role models for African American children, African American teachers felt they were examples of how to overcome challenges to be successful in life. Many African American teachers shared the lived experiences of their students. Because of this, they felt confident teaching students about challenges of discrimination and, at times, poverty, and were well-positioned to help students understand what it takes to be successful in this world. The teachers often felt an obligation to go beyond teaching solely academics and to educate the entire child, including character-building and helping with everyday life skills.

More than ever, it is so important to highlight the achievements of African American educators in the teaching profession. Not only is it critical to give them long-overdue recognition, but it helps to remind us of how far the educational system has come — and how far we have left to go.

As African Americans in Chester County we should be at the forefront of acknowledging how much the African American community has endured being an active part of the American education system.

In 1675, Sir Isaac Newton wrote these words to a fellow scientist—“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” We have all seen further, learned more because of the teachers, mentors, and supporters who have made the education of African American children possible. Here are the African American faculty, mentors and supporters of Chester County Training-Vincent High School and Schools in the County.

African American Principals of Chester County Training-Vincent High School

African American principals were committed to the education of African American children, worked with other African American leaders to establish schools for these children, and worked in African American schools, usually in substandard conditions.

It was the African American principal who led the closed system of segregated schooling for African Americans, primarily in the South. The African American principal represented the African community; was regarded as the authority on educational, social, and economic issues; and was responsible for establishing the African American school as the cultural symbol of the African American community.

The educational philosophies of African American principals generally reflected the collective beliefs of the African American communities that believed education was the key to enhancing the life chances of their children. Particularly in many small southern towns, the African American school was the institution that reinforced community values and served as the community’s ultimate cultural symbol. African American principals served as models of “servant leadership.”

Savage (2001) research findings indicated that African American principals “did more with less” with respect to providing an education for African American students. That is, even without money or resources, African American principals operated and maintained schools for African American children. Savage noted that African American principals operationalized agency in three ways: (a) developing resources (acquiring money, materials, and other resources to ensure the success of the school), (b) performing extraordinary services (maneuvering district policies, introducing new curricula and activities, and instilling in African American children resiliency, self-reliance, self-respect, and racial pride), and (c) focusing on the school as the center of the community (transforming schools into the cultural symbol of the African American community).

Their passive and direct resistance to overt hostility included working around discriminatory policies. They worked to improve the quality of teachers in African American schools by recruiting qualified teachers. Educating African American children was the impetus for their actions, and the notion of “doing more with less” was the core of their agency in preparing students for immediate and future success. African American principals understood and worked within the existing power dynamics and acted as “middle men.”

Here are some of the principals of Chester County Training-Vincent High School

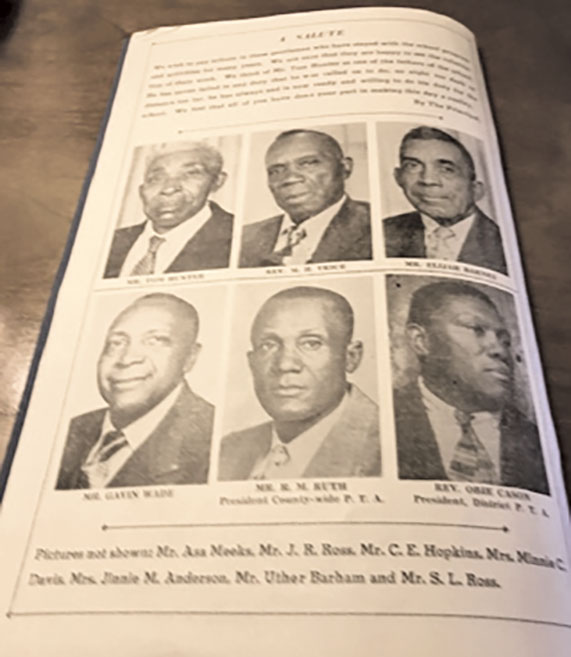

African American Men Who Supported Education

in Chester County

A salute and tribute to the following gentlemen was given at the April 7, 1950, dedicatory exercises of Chester County Training School. These are the gentlemen who stayed with the school program and activities for many years. They were able to see the culmination of their work. A special thank you was given to Tom Hunter as one of the fathers of the school. He never failed in any duty he was called on to do, no night too dark or distance too far, he was always ready and willing to do his duty for school. All the following did their part in making the building of the Chester County Training School a reality.

African American PTA Groups in Chester County

All parent-teacher and family-school partnerships advocate for the welfare of students. However, we often view the focus of a PTA as much narrower. While parent-teacher groups like PTAs and PTOs directly support the school community and encourage parents to get more involved in their child’s education, in every case, the focus is on the adults supporting kids.

Regardless of what type of parent-teacher group you participate in, there is a greater opportunity to work together with your school’s administration. Collectively, you can create a higher level of student education and personal well-being that will help students develop into better, more well-rounded adults.

Parent-teacher groups have long positioned themselves as organizations operating in the best interests of all schools, students, and teachers. In the 1890s, African American teachers in the segregated schools of the U.S. South were already engaged in founding school-improvement societies to support the rural schools at which they taught. Many school-community groups for segregated schools were created in the early decades of the 20th century, which resulted in the founding of several black PTA branches. Its efforts went primarily into raising funds for their schools. In the first half of the 20th century, because segregated schools were grossly underfunded, black school-community groups relied heavily on fund-raising.

At the turn of the 20th century there was a time of progressive reform in schools and society, when citizens believed they could remake the world through better education, efficiency in schools, and an educated parenthood. Nowhere was this expression as heightened as in the many PTA groups that increased greatly in number. The African American PTAs in Chester County were a vast network of action and communication. They aligned parents and teachers more closely than we tend to think, with the two groups in many instances working closely side-by-side.

The PTA was founded upon and has continued to sustain in so many places-namely, that schools belong to their communities and are united around efforts to improve education, life, and civic engagement. Membership in African American PTAs in Chester County was open to anyone who wanted to be involved and make a difference for the education, health, and welfare of children and youth in Chester County.

During this time, local parent-teacher associations were responsible to their various schools. Their initiatives ensured school lunches were served, water fountains were installed, and curtains for the stage at Chester County Training-Vincent High School, stoves, and refrigerators, etc. in county schools. Here are the PTA groups of Chester County.

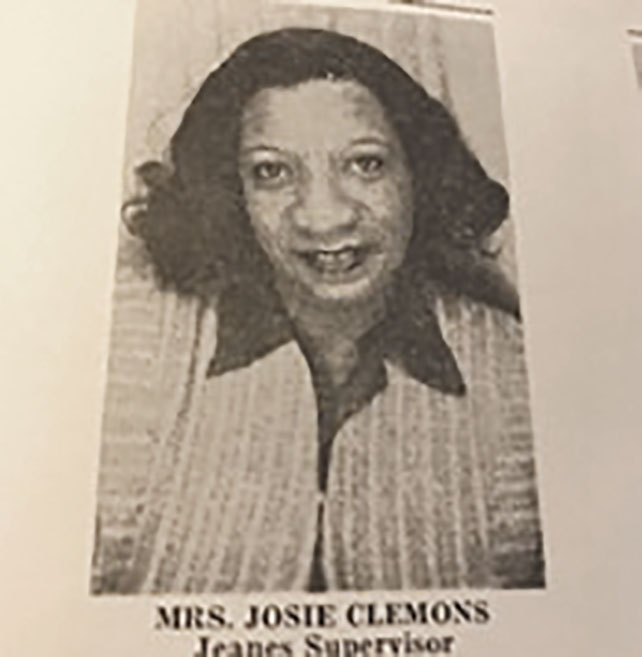

Jeanes Supervisors

In 1907, philanthropist Anna T. Jeanes, a Quaker philanthropist, created an endowment fund of $1 million. The fund was intended to assist community, county, and rural schools for African Americans in the southern United States. Jeanes named Booker T. Washington and Hollis Burke Frissell to head up the fund and directed them to appoint a board of trustees to manage it. The fund was called the Negro Rural School Fund, or Jeanes Fund.

The Jeanes Supervisors were a group of African American teachers who worked in southern rural schools and communities in the United States between 1908 and 1968. Approximately 2,300 Jeanes Supervisors worked in 16 southern states. The fund educated and hired black teachers and traveling supervisors for rural schools and improved African American school facilities.

According to (William, 1979) Jeanes Supervisors had no specific job descriptions. A Jeanes Supervisors motto, of unknown origin, was: “Doing the Next Needed Thing.” Jeanes Supervisors helped families plan arrangements to bury loved ones, built pit toilets, and organized health department vaccinations for school children. They also taught women in the community how to plant gardens and can vegetables, raised funds for a new school, and helped teachers develop lesson plans.

(Dale, 1998) says typically, Jeanes Supervisors emphasized community self-help. Instruction in both industrial and academic school subjects highlighted the use of inexpensive, easily obtained objects both at home and in teaching at school and maintained the good will and support of the community. Industrial education, or manual training, particularly skills such as bricklaying, sewing, and food preparation, was generally emphasized in African American education during this time rather than academic training. Jeanes Supervisors submitted monthly reports to their superintendents and to the state agent for Negro education and held annual exhibits of industrial work by community parents and students.

School integration in the 1960s effectively ended the Jeanes Supervisors’ memorable role in southern rural education for blacks. But during its life, the Jeanes program improved education for African American children. They provided in-service education to improve their teachers’ professional skills, and they worked to help their counties’ schools become accredited. They also gave strength and hope to black communities that often lacked both.

Other Supporters of African American Education in Chester County

According to J. Manley Trice, principal of Chester County Training-Vincent High in 1950, a thank you was given to the superintendent, Board of Education, and state officials in the dedicatory exercises of Chester County Training School. As Principal Trice states, “We feel without the very fine cooperation and understanding of our superintendent Tom Armour, Board of Education, and the Chester County Court this beautiful structure we dedicate here could not have been possible.”